Since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision in June 2022, states have become the settings of hotly-contested fights over abortion policy. Ohio has been perhaps the most closely-watched battleground, as it held not one, but two referenda related to abortion in 2023.

Ohio has a process for citizen-initiated changes to the state constitution. First, citizens must gather signatures of support for their proposed amendment amounting to 10% of the turnout in the most recent gubernatorial election. These signatures must be collected from at least half of all Ohio counties. Once these signatures are counted and verified, the proposed amendment is placed on the election ballot and must receive a majority of votes to pass.

In February 2023, pro-choice activists filed paperwork to begin this process with hopes of enshrining abortion rights into the state constitution in the November election. Fearing the eventual success of this effort, Republican legislators voted to call an August special election in which voters would be asked if they wanted to change the constitution to make it more difficult for citizen-initiated constitutional amendments to pass. Specifically, the lawmakers proposed raising the threshold for passage from a majority to 60%. They also sought to require that signatures be gathered from all counties rather than half, and to eliminate the brief period that citizens were allowed to gather more signatures if it was determined that they had come up short. The stage was set, then, for two elections that would decide the future of abortion access in Ohio (while the August election was not explicitly about abortion, both sides recognized that it was an attempt to thwart the passage of the pro-choice activists’ proposed amendment).

The pro-choice side won by landslide margins in both elections: 14.2% points in August and 13.6% in November, statewide.

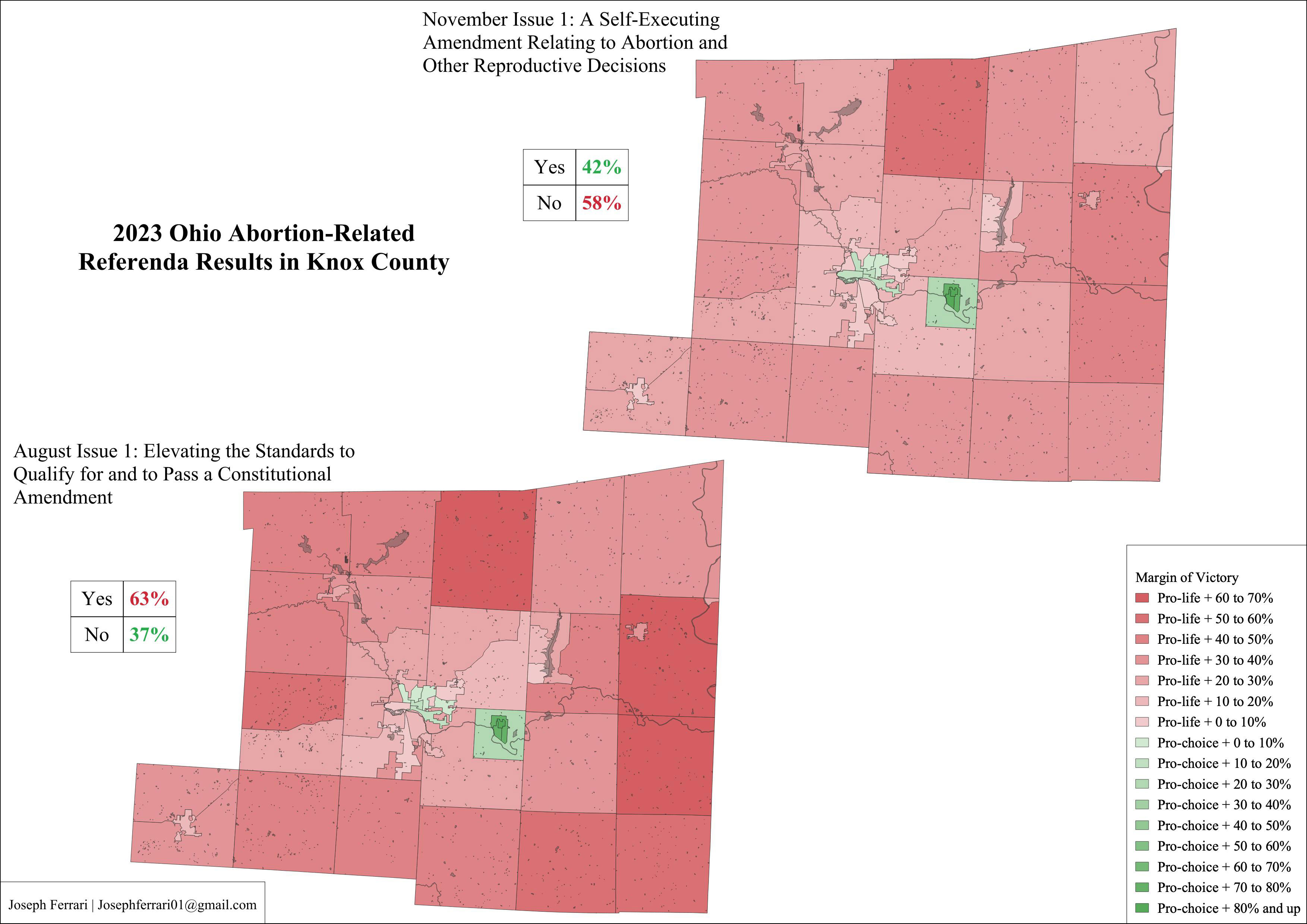

The pro-life side won Knox County both times. This is unsurprising given the county’s conservative lean — the last time that Republicans failed to win the county on the presidential level was in 1964. But while the pro-life side won Knox County twice in 2023, they did so by much less the second time — by only 15.8% in November compared to their 25.1% margin in August. The following graphic shows the precinct-level results of both elections in the county.

Why did Knox County swing 9.3% points in the pro-choice direction between these elections while the state shifted slightly the opposite way, by 0.7%? If anything, one would have expected a conservative county like Knox to be less supportive of the November ballot question (which was more explicit about protecting abortion rights). The opposite turned out to be true.

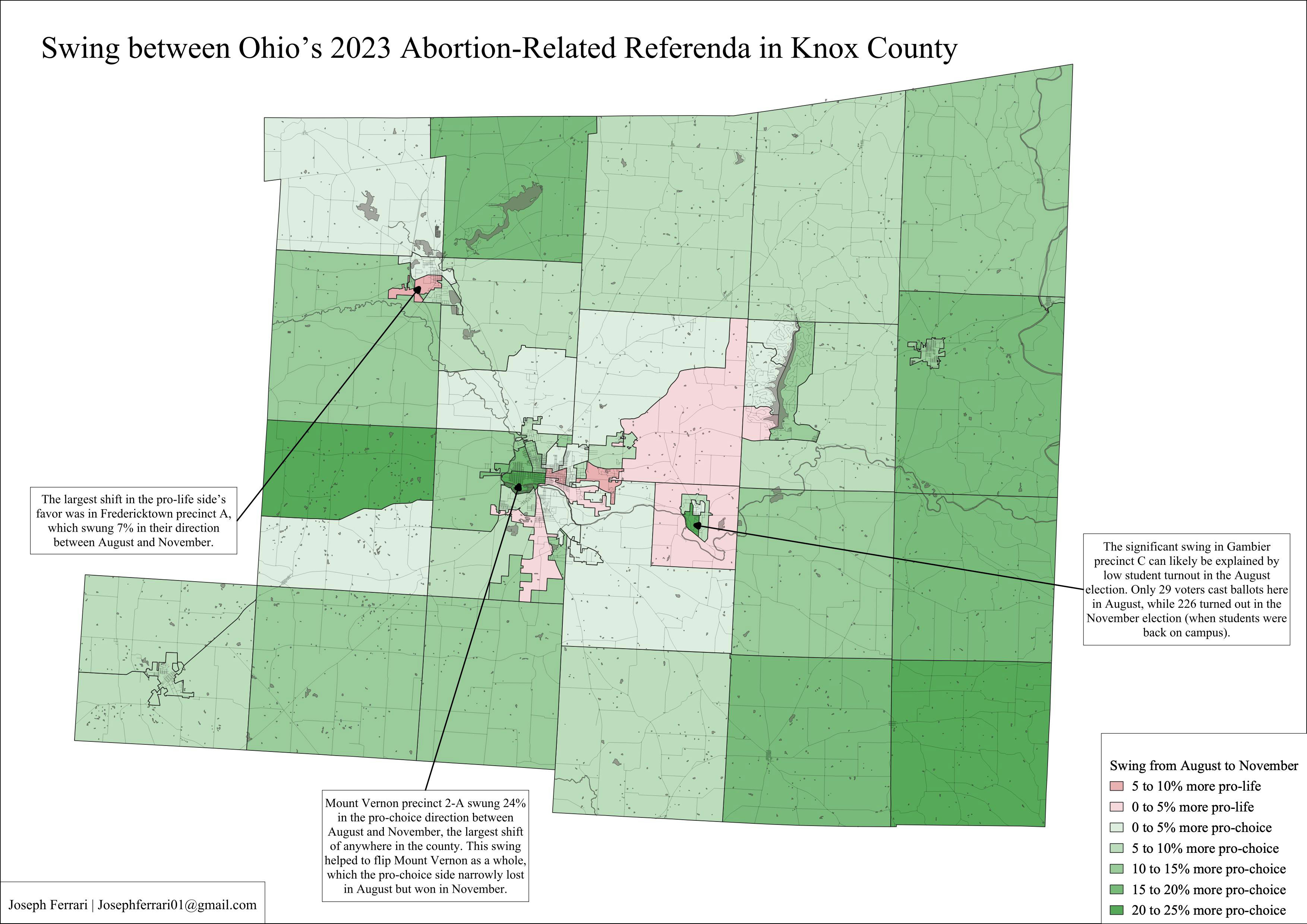

One hypothesis is that left-leaning Kenyon student voters failed to cast ballots in the August election (because they were on summer break), but turned out in full-force in November (when they were back on campus). It is true that Gambier turnout was much higher in November than August. In the combined Gambier precincts (which include townspeople as well as students), only 262 votes were cast on the August abortion question compared to the 695 cast on the issue in November. We can find out what impact this differential turnout had on the countywide result by excluding the Gambier precincts from the final tabulation. By excluding Gambier from the August election results, the pro-life side’s margin of victory countywide increases by 1.5%. Doing the same in November, meanwhile, increases the pro-life side’s margin by 3.3%. The difference between these two percentages (1.8%), then, is how much differential turnout in Gambier contributed to the pro-choice swing between these elections. What explains the rest of the 9.3% swing in Knox County, then? The following map shows how things shifted under the surface, on the precinct-level.

The shift in the pro-choice direction was overwhelming, with 46 out of 54 precincts swinging this way. In some places, the shift was quite dramatic. Mount Vernon precinct 2-A, for example, voted 24% more pro-choice in November than August (leading the pro-choice side to win it in the second election). This is a precinct that Donald Trump won by 39% in the 2020 presidential election. In fact, he (and J.D. Vance for that matter) triumphed in all of the precincts that the pro-choice side won, except those in Gambier.

So the story here is not only the pro-choice swing between August and November, but also how much more popular the pro-choice position is than the Democratic politicians who espouse it. The results point to the existence of a significant number of voters who regularly support Republicans, but who believe that abortion rights should be protected. Capturing these voters will no doubt be a priority for Democrats in 2024 and beyond.

Joseph Ferrari ‘24 is a senior associate at the Center for the Study of American Democracy, who majors in political science. When not thinking about politics, he sings with the Kenyon Chamber Singers and the Männerchor tenor/bass classical a cappella group.