When a car full of Kenyon faculty and staff pulled up to the home of 93-year-old Allen Ballard ’52 H’04 just outside of Albany, New York, he knew exactly how to make them feel welcome.

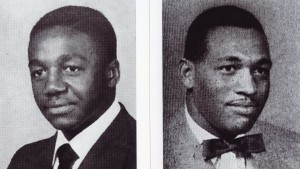

The former student body president, who was one of the first two African American students to graduate from the College, pulled out his harmonica during the visit and played “Kokosing Farewell.”

“I think I'm gonna give you a little concert,” the nonagenarian told the group almost exactly a decade after he serenaded the campus community with his voice and guitar at Kenyon President Sean Decatur’s inauguration.

His three guests made the trip to honor him for his contributions to integrating Kenyon — along with fellow student-athlete Stanley Jackson — and his later professional accomplishments.

When the inaugural Allen B. Ballard Prize in African Diaspora Studies was given in the spring, its namesake was unable to attend. So this November visit was a chance for Kenyon to come to him.

“The pioneering efforts of Allen Ballard and Stanley Jackson paved the way for many African American students, faculty, and staff,” said Chris Kennerly, dean for diversity, equity and inclusion, who made the trip and presented Ballard with an award commemorating the African Diaspora Studies prize being named in his honor. “There’s a lot that we owe to both of them.”

Ballard arrived on Kenyon’s campus in 1948, playing football and lacrosse. He graduated magna cum laude with a political science degree and studied in France as a Fulbright scholar. Later, he earned a doctorate in government with a specialization in Soviet politics from Harvard. He is currently an emeritus professor of history and Africana Studies at the University at Albany, SUNY.

In the 1960s Ballard designed a program to help desegregate the City College of New York, opening its doors to more Black and Puerto Rican students from surrounding neighborhoods. This quickly became the direct model for new equal opportunity programs at dozens of New York colleges.

After joining the University at Albany, SUNY in 1986, Ballard taught Russian history, African American studies and civil rights, while being active in that university’s educational opportunity program.

Ballard said he was excited by the recent visit and humbled by his connection to the new award, given to a Kenyon student in recognition of an outstanding scholarly project that promotes understanding of the history, cultures and peoples of the African diaspora by focusing on issues pertaining to social justice.

“I really appreciate it,” he said. “And it was great having them and just seeing some folks from Kenyon and talking about old times.”

He described his time on the Hill as very positive, though it could be challenging.

“It was a bittersweet four years,” he said. “Sweet in a sense that we had a great education, both of us [Ballard and Jackson]. And I made lots of great friends at Kenyon. On the other hand, the fraternity discrimination left its mark. I played ball with fellas, but when it came time to socialize, they were in their [all-white] fraternities and I was an independent.”

Upon his graduation in 1952, Ballard became part of the historically African American fraternity Omega Psi Phi — which Kennerly also joined years later. The latter taught Ballard the fraternity’s secret handshake when they met at Decatur’s inauguration and refreshed his memory during their recent visit.

“He said, ‘But you’ve got to show me the secret handshake again,” Kennerly recalled. “That’s special to me.”

Kennerly, who organized the trip to visit Ballard, was joined by Sylvie Coulibaly, associate professor of history and chair of African Diaspora Studies, and Jonathan Tazewell ’84, Thomas S. Turgeon Professor of Drama and Film and chair of the Department of American Studies, who filmed the encounter.

Coulibaly said it was a top priority for her to create a prize recognizing the work of Kenyon students in African Diaspora Studies and that Kennerly was instrumental in helping to honor Ballard through it. Naming the award after Ballard calls attention both to his role in the integration of the College and his esteemed career as a historian of the African Diaspora who promoted the field tirelessly.

“The establishment of the prize recognizing African Diaspora Studies and the example of resilience set by Allen Ballard while he attended Kenyon and his accomplishments as a scholar are a source of inspiration and of pride for our Black students, as well as for faculty and students of all nationalities and ethnicities,” she said.

Tazewell said he loved listening to Ballard’s stories, which were told with wit and zest and which described the closeness of his relationships with the Black community of Mount Vernon.

“His demeanor is amazing. He is sharp as a tack,” he said. “His memory, the stories that he told are just so interesting and powerful.”

Tazewell said he was touched by Ballard’s positivity in the face of adversity and how he embraced his role as a changemaker throughout his life. Naming the Kenyon prize for him is an important way of making sure that this legacy lives on, he said.

“He is a professor, he is a scholar, he is an activist, too,” he said. “He had a lot to do with breaking down barriers of segregation in education, and I think that’s really important. That’s to be remembered by this institution. I want it to be more well known that he has made this really significant contribution to Kenyon.”

Ballard is the author of two nonfiction books, “The Education of Black Folk: The Afro-American Struggle for Knowledge in White America” and “One More Day’s Journey: The Story of a Family and a People.” His fictional writings include a novel about Black soldiers in the Civil War, “Where I’m Bound.”

As a Black man who attended Kenyon decades after Ballard, Tazewell said it’s important to keep working for change, and the elder man’s example serves as a great reminder for current students.

“Until you feel like there is no challenge that is based upon your identity, we are not done,” Tazewell said. “Dr. Ballard is a big part of that, the beginning of the lineage of fighting for this place to be everything that we want it to be — open to all kinds of ideas and devoid of any kind of the legacy of racial oppression or discrimination.”

Eliza Wetmore ’23, the first winner of the prize that bears Ballard’s name, said the award is a great starting point for familiarizing today’s students with his legacy.

“It’ll be a great introduction to him for the campus,” she said. “It’s a great honor to continue carrying on his legacy through my work.”

These days, Ballard busies himself writing about the current political landscape, baking bread, exercising and practicing on a flight simulator.

“I always wanted to be a pilot, but my balance wasn’t good enough to get into the Air Force,” he said. “But I’ve always been fascinated by aviation.”

His advice to current students is simple — because some things never change.

“Take advantage of these beautiful four years,” he said. “And get to know yourself and the world. … Engage in things that seem alien to you.

“Just enjoy yourself,” he concluded. “But not too much!”