Besides the Office of Institutional Research (IR), many individuals and groups on and off of our campus conduct surveys of Kenyon students. The number of invitations to participate in online surveys has increased dramatically, making it more important than ever for surveys to be carefully thought through in order to remain effective analytic and research tools.

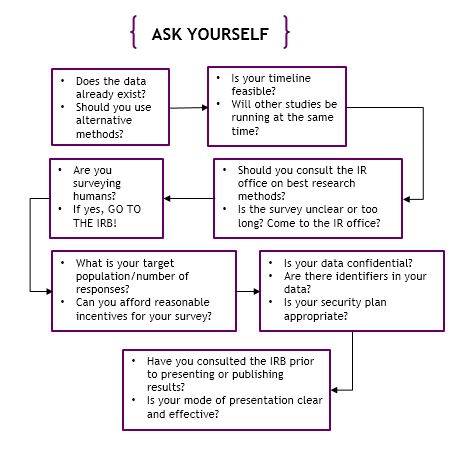

For those who are interested in conducting a survey at Kenyon, we recommend that you consider the following questions before administering the survey. Please contact IR if you are surveying a large population of Kenyon and/or conducting a survey for non-academic purposes.

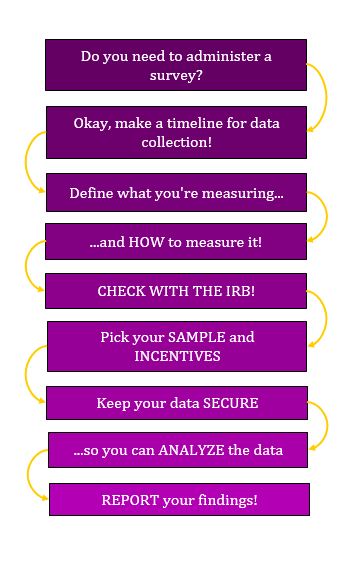

The whole process of administering a survey will follow the format outlined by the flow chart listed below.

For more detail on any of the above points, read more below:

1. Do you really need to conduct a survey

2. Developing a reasonable timeline

3. Defining your questions

4. Designing the survey instrument

5. IRB review is likely necessary

6. Selecting the sample

7. Considering incentives

8. Collecting data: data security

9. Analyzing and reporting the results

1. Do you really need to conduct a survey?

Kenyon College regularly administers large surveys to undergraduate students at various stages during their years at Kenyon. Those questionnaires and many results are available on the IR website for your review. Here is a list of topics covered by recent Kenyon surveys.

The data we collect are archived and can be used to evaluate a wide variety of questions relevant to campus life and student development. IR can help you consider ways in which the available data can address your questions. For more information about this, contact IR.

You may also want to consider alternative methodologies for collecting relevant data such as focus groups and face-to-face interviews. These approaches have important advantages and may be a better choice than a survey if you are exploring a topic about which relatively little is known (in which case, it would be difficult to develop appropriate survey questions) and/or you would like to elicit candid, in-depth information.

2. Developing a reasonable timeline

It is easy to type survey questions into web survey software, and bulk emails can be sent with the click of a button. That should not imply, however, that a quality survey can be turned out quickly. Give yourself ample time—four to six months is not unreasonable—to develop a questionnaire that makes sense and is not overly burdensome on the respondent in terms of survey length and difficulty. Survey instruments should be “pre-tested” on a small number of subjects from the population of interest and revised on the basis of their feedback. In addition, you will need to allow time for your project to be reviewed by various constituents within the College, for the printing or programming of your instrument, and for the actual dissemination of the survey to its intended respondents. A survey that meets a tight deadline by cutting corners may miss the overall objective of providing useful data.

Surveys should usually not be administered during periods of peak workloads, or during vacations or holidays. In general, more surveys are run during the spring semester than during the fall, so it might be advantageous to considering fielding a survey in the fall.

Check the Calendar of Campus Surveys to minimize respondent survey fatigue and potential conflict with other surveys. Contact IR to have your survey added to this calendar so that others can work around it.

3. Defining your research questions

While this may seem too obvious of a step to mention, it is a critical part of the research process. Take the time to clearly define the research questions you want to address. Check in with colleagues and relevant decision-makers to elicit their thoughts on important questions to address. Review the literature on your topic to see how questions have been framed by other researchers, and what related issues or themes should be taken into consideration when exploring this topic. The ERIC (Ovid) database which is accessible through the “Databases A-Z” tab of the Kenyon Library webpage is a good place to begin a search for literature on higher education topics. Professional associations affiliated with your area of practice also often maintain links to current literature in the field.

4. Designing the survey instrument

The content of the survey stems directly from your research questions. Still, great care is needed to develop survey questions that will effectively and efficiently elicit the information you want. Ideas for specific survey questions can come from existing instruments, colleagues, members of the target population (collected via focus groups or interviews), and your own observations. It is important to balance adequate coverage of your research questions (comprehensiveness) with conciseness. Avoid the temptation to include questions that may provide interesting but not particularly useful results. Also, consider whether some of the data you want is available through other sources such as institutional files.

Surveys should begin with a statement that clearly explains:

- The purpose of the survey

- That participation in the survey is voluntary

- That the respondent can skip questions they would prefer not to answer

- Whether responses provided will be treated as anonymous or confidential data

- How information from the survey will be reported and used

When composing survey questions, here are some general guidelines to bear in mind:

- Survey questions should not be “leading” or contain jargon or technical terms that may not be understood by all respondents

- Response categories should reflect a comprehensive array of choices, including “not applicable,” “don’t know” and/or “other” where appropriate

- Limit the use of open-ended questions; as much as possible, position these at the end of the survey instrument

- Short surveys generate more responses and minimize the imposition on the valuable resource of our students’ time

- Surveys that skip respondents over questions that are not relevant feel shorter and more pertinent to the respondent

Survey methodologists specialize in the construction of survey questions and their response categories. Consider having someone with survey design expertise review your survey instrument. As mentioned earlier, it is very important to pretest your survey instrument with a subset of your target population. This provides a critical test of the clarity, comprehensiveness, and length of your survey.

Are you planning to conduct a web-based survey? If so, you will need to select an appropriate survey vendor. In addition to the programming and hosting services provided by a potential vendor, you need to know how they safeguard the identity of your participants and security of the data collected. Kenyon maintains a license with Qualtrics and recommends using their survey tool.

5. Institutional Review Board review may be necessary

If your survey can be considered “research,” it needs to be reviewed by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Kenyon. This process may take two weeks or longer.

According to The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, “research” generally includes any ”activity designed to test an hypothesis, permit conclusions to be drawn, and thereby to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (expressed, for example, in theories, principles, and statements of relationships).”

In general, surveys related to academic course requirements (i.e., theses) and surveys that produce data that will be presented at or published in off-campus venues will require IRB review and approval. New analyses of existing data may also qualify as “research” in IRB terms. Administrative surveys should also ask for the appropriate level of review from the IRB.

Contact the IRB for further information.

6. Selecting the sample

It is not necessary to survey an entire population in order to have valid, generalizable results. A random sample will do the job while minimizing costs—including the costs of survey fatigue. Consider that many excellent national polls and studies include only 1,000 individuals from across the entire country. If you need help determining an appropriate sample size for your project, you may contact the IRB for assistance. Texts on survey research design provide guidelines for setting sample sizes, and sample size calculators are also available on the internet.

7. Consider incentives

Many campus surveys offer respondents the chance to be entered into a raffle drawing for prizes. Gift cards and personal electronic devices are common prizes. The literature on survey methodology suggests that these kinds of incentives have a modest impact, increasing the response rate slightly.

Surveys that offer incentives to respondents must track respondent identities in some way. If identifying information (such as names, email addresses, or student identification numbers) are kept with the survey responses and confidentiality is promised to respondents, the study needs a security protocol for keeping the data safe (see next item).

8. Collecting data: data security

Survey respondents need to be told if their responses will be anonymous, kept confidential, or are entirely non-confidential.

Anonymous data do not include names, addresses, student identification numbers or any other personal information that would make it possible to associate a response with any given individual.

Data that are confidential contain information that may identify an individual respondent. There are significant advantages to collecting identifiers, including the ability to do “pre and post” studies through linked data files. However, files containing individual identifiers must be stored with great attention to data security and access. If you plan to collect confidential data, contact the IRB for more information on developing a security plan.

9. Analyzing and reporting the results

Before you begin your survey, develop a plan for analyzing the data and reporting the results. How will you use the data you collect? With whom will your results be shared? In what format will results be shared – as visual presentations, written or electronic reports?

At a minimum, most reports of survey results provide a full set of frequencies for each question. Cross-tabulations of responses across subsets of respondents are also useful, although care must be taken to protect the privacy of individuals’ responses. A general rule of thumb is not to report results for categories containing five or fewer respondents. Remember that survey results cannot be presented or published beyond Kenyon without IRB approval. Be sure to review what IRB approval entails.

Consider how you might share your results with others on campus who are interested in related questions. By sharing your findings widely, you can not only enlighten the campus community about your work, but you may also be able to head-off a new data collection effort.