This season, workshop faculty, staff and editors at the Kenyon Review shared reading recommendations of works that inspired and challenged them. In uncertain times, burying oneself in an engaging read can be a comfort like no other. Happy holidays, and happy reading!

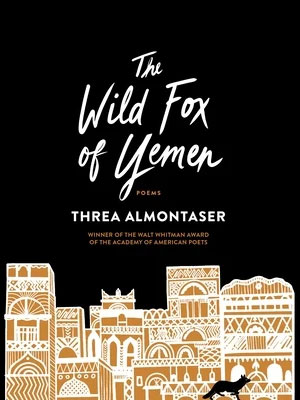

Victoria Bosch Murray, editorial reader

At dinner with a poet, he said he was reading and teaching "The Wild Fox of Yemen" by Threa Almontaser (Graywolf Press, 2021). Now I'm immersed in it, her voice so specific and beautiful! I’m passing her on to you.

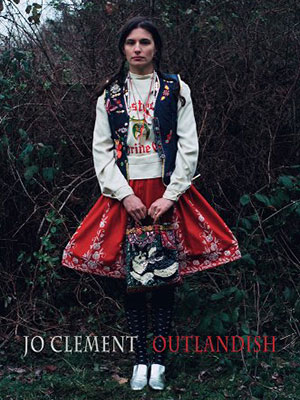

Tina Cane, adult writers workshop faculty

I am not sure how I stumbled upon Jo Clement's "Outlandish" (Bloodaxe Books, 2022), but I am delighted that I did. It's riveting. Clement's voice is instantly distinct, as she harnesses deep music and arresting imagery to evoke Roma cultural traditions and legacy. The poems feel ancient yet contemporary, fable-like and otherworldly. The magical landscape of Clement's imagination is a place where "pine pollen scuds the air," and where "a tree set in concrete" meets girls who ride "leaning gravestones like ponies." Myth-like yet working to dispel myths, this collection reads like a fistful of diamond bits scattered on a patch of parched earth. Dazzling and sharp to quench a curious thirst.

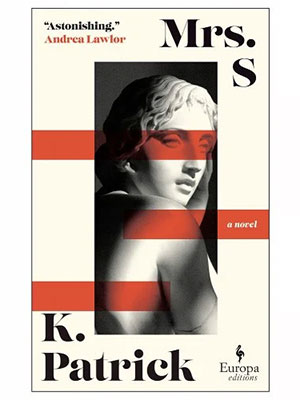

Frances Cannon, editorial reader

I would like to suggest a pairing for winter reading — two books with similar themes and moods written in very different time periods: "Mrs. S" by K. Patrick (Europa Editions, 2023), and "The Well of Loneliness" by Radclyffe Hall (Jonathan Cape, 1928). Both books are set in dreary English countryside, yet they pulse with longing, featuring relationships thwarted by the gender identities of the main characters. There are also many parallels in the scenery and imagery of each book — characters wrestle with their desires while wandering through rose gardens, or over tea in grand old stone houses. The primary difference between the books is the public reception at the time of publication: "The Well of Loneliness" was ruled as obscene by British courts, while "Mrs. S" is attracting glowing reviews and accolades.

"The Well of Loneliness" follows Stephen Gordon, who is given a boy's name despite her parents' disappointment at her gender at birth. She is raised in the bosom of wealth with a loving father and a cold mother. After her father's death, she takes control of the estate and explores her affection for an American woman who moves to the area with her husband. I won't spoil the consequences of their dalliance here, but you can imagine how a book written in 1928 reflects the social restrictions and the "conspiracy of silence" of the Victorian time period.

"Mrs. S" follows a young Australian woman, who is hired as "matron" to an elite English boarding school, where the legacy of an unnamed "dead author" looms large. My reading is that the school is modeled after Roe Head school, where Charlotte Brontë taught. Our also-unnamed main character falls dangerously for the headmaster's wife, who engages with this secret desire, but only within the bounds of her marriage and position of power at the school. I will also refrain from spoiling the results of their tryst, but I will say that if you take my advice to read these books as a pair, you will find parallels from cover to cover, despite the century that divides the two texts.

Jennifer Galvão, Kenyon Review Fellow

Eliza Clark's "Penance" (Harper, 2023) spoofs and skewers the true crime genre even as it exploits the form's pleasure and readability. Presented as a work of nonfiction, Penance examines the fictional murder of a Yorkshire teenager, who is tortured and set afire by three of her high school classmates. Told through podcast transcripts, diary entries, long-form interviews and the imaginative leaps of Clark's fictional investigative journalist, "Penance" tells a story about consumption: "Did you see the article about her, buried in the chumbox of an already disreputable website? Did you see the red-headed, stock-image model juxtaposed against an edited, charred corpse captioned: 'You Won't Believe What They Did to Her'? Did you listen to a podcast? Did the host make jokes? Do you have a dark sense of humor? Did that make it okay?" Brutally funny, Penance is never condescending in its treatment of teenage girls and their private lives on the internet — instead, it reads like a true period piece of early 2010s tumblr.

Shannon Gibney, adult writers workshop faculty

"How to Say Babylon" by Safia Sinclair (37 INK, 2023) is a stunning exploration of ancestry, culture, Black politics and language — all through the lens of Rastafarianism. Sinclair, an accomplished poet, narrates her often tenuous relationship with her Fundamentalist Rastafarian father, who is himself attempting to find his way through Jamaica's unresolved and deeply unequal colonial history. The central struggle in the book is Sinclair's journey to find her own voice as a young woman in a religion that does not see women as equal. And also to situate her own personal and family history within the larger struggle for Black liberation in Jamaica and beyond. All of these layers are probed through precise and powerful language, creating a reading experience that is both intimate in its depth and vast in its scope.

Geeta Kothari, senior editor

My reading has been all over the place this year, something old and something new. I'm generally not a fan of biographies, but "Flaubert and Madame Bovary" by Francis Steegmuller (New York Review Books, 2004) has been a strange page turner, more artfully crafted than the average biography.

Nicole Chung's "A Living Remedy" (Ecco Press, 2023), a beautifully written memoir about the deaths of her parents, has stayed with me since I read it. It's as much about grief as it is an indictment of our broken health care system.

Cindy Juyoung Ok, Kenyon Review Fellow

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint's "Names for Light" (Graywolf Press, 2021) writes from what cannot be cataloged of birth and burial, letters and translations, and, like all the best memoirs, memory itself — names that mean light, and names that are toward light.

Alyssa Quinn, editorial reader

I haven’t been able to shut up about "Emergency" by Daisy Hildyard (Astra House, 2022) since reading it a year ago. This book is a pastoral novel for the Anthropocene. Recounting her childhood in rural Yorkshire in the 1990s, the narrator describes a multitude of small moments in which the local and the global, the micro and the macro, reveal themselves to be stickily joined. In prose that is achingly precise and meticulously crafted, Hildyard captures the stunning specificity of nonhuman beings, their sparkling and undeniable presence, while also deftly sketching their enmeshment in countless larger structures — the currents of the ocean, the supply chains of global trade, the circulation of pesticides through an ecosystem. Through her extraordinary capacity for sensory awareness and multi-scalar thinking, Hildyard’s narrator renders the world strange again in beautiful, awful and uncanny ways. An astonishing and essential read.

Misha Rai, contributing editor

I am so excited to begin my list of winter recommendations by celebrating the debut books, a novel and a short story collection, by two writers, Marcela Fuentes and Ananda Lima, who have both been previously published in the Kenyon Review.

"Malas" by Marcela Fuentes (Viking Press, 2024) is a stunning family saga spanning three generations, following a family that lives on the Texas-Mexico border. This is an emotionally intelligent and moving story of revenge, punk music — the band in the novel is delightfully called Pink Vomit! — hidden desire, rebellion. Both a coming-of-age narrative and epic in its scope, "Malas" gives us Lulu Munoz, a character we will not soon forget.

"Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil" by Ananda Lima (Tor Books, 2024) follows a writer who sleeps with the devil — ill-fitting suit, faded orange wig, some bad foundation — at a Halloween party in 1981, and then keeps running into him as she writes stories that capture the same feeling Alice had as she fell through the looking glass. Here is a collection of stories that not only delights in its ability to subvert the reader's expectations but also leaves one haunted. I haven't stopped thinking of "Antropófaga," the story we published years ago.

One fun read I would recommend would be Maggie Bailey's "Seams Deadly" (Crooked Lane Books, 2023). This cozy murder mystery — I mean, it's literally a Measure Twice Sewing Mystery where one of the murders happens in a fabric store #1 (!) — is a perfect read for an afternoon on the sofa as the temperatures continue to drop outside.

"The Lengest Neoi" by Stephanie Choi (University of Iowa Press, 2024) is a debut collection of poems that won the esteemed Iowa Poetry Prize this year. Loss, language, location, learning are some of the predominant themes in this ambitious and beautifully written collection. There are poems here that linger in your subconscious long after you've put the book down.

Apogee Graphics has just released a perfect pocket-sized nonfiction book on composting by writer Cassandra Marketos called "Compost This Book." In this short, and small, book the reader goes on a composting journey, learning the mechanics of decomposition. As a new and now fervent practitioner of this art, I carry this book with me always on my journey to composting. The book itself is made up of recycled paper and is printed with vegetable inks.

Jackson Saul, managing editor

As I grow older, it becomes easier to profess my World War II reading habits — now more plausibly attributed to a cliché of male middle age than to the other cliché, of boyish immaturity. The "World War II extended cinematic universe" (to borrow a colleague's phrase) offers not only a mass proliferation of narrative but also uncountable places to find some bearing on the present, a present some may find too enigmatic or painful to confront head on. It gratifies and spurs me when such connections present themselves, and in recent months, I've looked to Anna Reid's "Leningrad: The Epic Siege of World War II: 1941–1944" (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012) for accounts of a civilian population in the grips of an annihilative blockade and, relatedly, Randall Jarell's damning verse ("we burned / The cities we had learned about in school… our bodies lay among / The people we had killed and never seen"), to Hannah Arendt's "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil" as much for a glimpse at accountability as for its titular concept, and to Heinz Heger's "Men with the Pink Triangle: The True, Life-and-Death Story of Homosexuals in the Nazi Death Camps" (Gay Men’s Press, 1980).

After completing "A Writer at War: A Soviet Journalist with the Red Army, 1941–1945" (Pantheon Books, 2006; a contextualized presentation of Ukrainian Jewish writer Vasily Grossman's journals and reporting by editor-translators Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova), I moved on to Grossman's novel "Life and Fate" (New York Review Books, 2006), rooted in the same experiences. In this baggy book, the peripheral, sometimes even one-off characters stick in my mind: the Ukrainian mother (likely one of multiple in the book based on Grossman's own, murdered in Berdychiv) writing an undeliverable letter to her son; the forced laborer and former accountant undermining an SS directive by muttering "bodies" under his breath after calling out each count of exhumed "items." Such human specificity draws us to fiction, but a morally clear, editorializing voice also finds occasions to emerge in these many chapters. I haven't made my way all the way through Robert Chandler’s 896-page translation, and I understand the faux pas of recommending a book you haven't finished, but I think here of what is often said of the people who "lived through history:" that they didn't know what would happen in the end.

Orchid Tierney, senior editor

Rich, haunting and lyrical, "Black Pastoral: Poems" by Ariana Benson" (University of Georgia Press, 2023) fractures the white fantasy of the pastoral, exposing at the center the entanglements between Blackness, identity and nature. Line upon line amplifies a call for an ecopoetics liberatory practice: "Never mind who once blistered / on the green and pleasant land. // There’s nothing you can tell me about beauty." And underneath this call, "Black Pastoral" invokes a mesh of love, hope and hurt in the pastoral to unmask a very human tenderness: "How tired I’ve grown of the trees… their seedy fruit ripened in rancor / their stagnation that passes for something like Humility."

Danilo John Thomas, assistnt managing editor

I am reading "The Doloriad" by Missouri Williams (MCD x FSG Originals, 2022). I recommend it for fans of stylish prose and free-indirect discourse; of films like "Mandy" and "The Bad Batch;" "Lord of the Flies" buffs; and anyone who likes their post-apocalypse run by a horde of incestuous, feral children.

Katherine Weber, senior editor

As a novelist I am particularly intrigued by the debut novels by my heroes, certain great writers whose books have been life-changing for me. Muriel Spark's "The Comforters" (J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1957) is an exemplar, a beguiling novel that heralded the astonishing books that followed. I've recently re-read Hilary Mantel's first novel, "Every Day Is Mother's Day," published in 1985 (Chatto and Windus). It's a dark confection, a weird and surprising story about weird and surprising characters. From first page to last in this truly odd book, you can glimpse the author teaching herself not only how to write a novel but also how to write a Hilary Mantel novel.

Tory Weber, director of youth programs

I recently read — and loved! — "The Bee Sting" by Paul Murray (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023) and "The Wren, the Wren" by Anne Enright (W. W. Norton & Company, 2023). I recommend them to anyone wanting to immerse themselves in a modern family saga. In both books, your understanding of the characters, their motivations, and their relationships to one another deepen and evolve as the narrative perspective shifts from character to character. Both authors use these shifting perspectives to explore the ways in which a family's history can scar and shape its members for generations, and I appreciated that both writers balance trauma and pain with a fair amount of dark wit. "The Bee Sting" is certainly the darker of the two novels — the whole book was permeated with a sense of impending dread and the ending is haunting me still. "The Wren, the Wren" ends on a lighter note, but I so enjoyed spending time in the heads of its funny and flawed female protagonists, that I was sad to turn the final page!

Books are available to purchase on the KR bookshop.org page.