It’s one thing for students to study the Holocaust; it’s another for them to connect with it on a personal level.

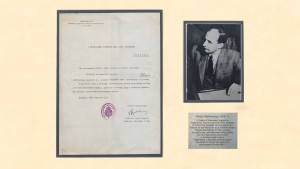

With the help of a unique collection of more than 2,000 artifacts related to the Holocaust housed in Chalmers Library, Kenyon students are able to go beyond the classroom and feel the impact of history through original letters, legal documents, photographs — even a dress with a yellow Star of David patch on it — that they can hold in their hands.

“There’s something really powerful for students to physically touch the items and not just look at them on a screen,” said Eve Kausch, outreach librarian for special collections and archives. “Especially now that there are fewer and fewer survivors of the Holocaust who are still living, being able to get a primary source, a firsthand account of something, is really important.”

For more than a decade, the Bulmash Family Holocaust Collection has enhanced learning in a wide variety of classes, from religious studies to European history and art history, according to Elizabeth Williams-Clymer, director of special collections and archives.

The collection was donated by Michael Bulmash ’66 P’14, beginning in 2012 and continuing through 2023. It includes items related to the rise of Nazism and Jewish persecution; the German occupation of continental Europe and Jewish extermination; aid and rescue during the Holocaust; and those who survived after Germany’s surrender.

In an introduction to the collection that appears online, Bulmash wrote that the artifacts are meant to serve as a memorial to members of his family who died in the Holocaust and as a resource for students, teachers and researchers in a variety of disciplines.

Max Ehrenfreund, a postdoctoral fellow in the Center for the Study of American Democracy and the Departments of Economics and History, asked past students to engage with the collection as part of a seminar about daily life in Nazi Germany and will do so again this semester for a class on modern Europe.

It’s been helpful, he said, both in teaching the importance of using primary sources as evidence to understand the past and present and as a way of connecting with the past.

“When the students have the opportunity to see the documents and handle them for themselves, the events that we talk about in class become more real and more personal to them,” he said. “It’s a very powerful experience for all those students.”

Professor of History Eliza Ablovatski uses the collection in her classes every semester in classes covering topics from refugees and migration in Europe to Freud’s Vienna to German history. It’s particularly useful, she said, because of its variety, touching on numerous countries during periods before, during and after World War II.

“The variety is what makes it so valuable for teaching,” she said. “I take a lot of different classes (to the collection) and I have the students do different things with that experience, but I find that it’s always something the students carry with them. It makes a big impression on them.”

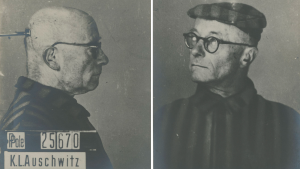

While many of the documents are in foreign languages — especially German — the photographs are particularly compelling to students because they speak for themselves, according to faculty.

One of those photographs made headlines recently after a historian used AI to identify the killer in a famous 1941 image. Known as “The Last Jew in Vinnitsa,” it shows a man kneeling at the edge of a pit filled with bodies, about to be shot by a Nazi soldier.

The image in the Bulmash collection is not the original but rather one distributed by United Press International. It has been digitized by Kenyon — like nearly all of the collection — and was linked to by a November New York Times story about the recent news. That image was accessed more than 250,000 times in the weeks that followed.

For Kausch, there’s great value to these sorts of virtual interactions, even for those who can’t handle the items personally.

“We’re in an era where history is kind of being erased and taken down from places on the internet, and this is an institutional repository that we have control over,” they said. “We’re dedicated to maintaining and keeping public access.

Ehrenfreund echoed those sentiments, citing the current of historical revisionism sweeping the globe, despite annual remembrances like those that will take place Jan. 27 on International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

“We live in a time when prominent politicians in Europe, as well as media personalities with outsized influence, are minimizing the Holocaust, denying its relevance to politics today, or denying that it happened altogether,” he said. “That context makes this kind of work incredibly important for the students.”