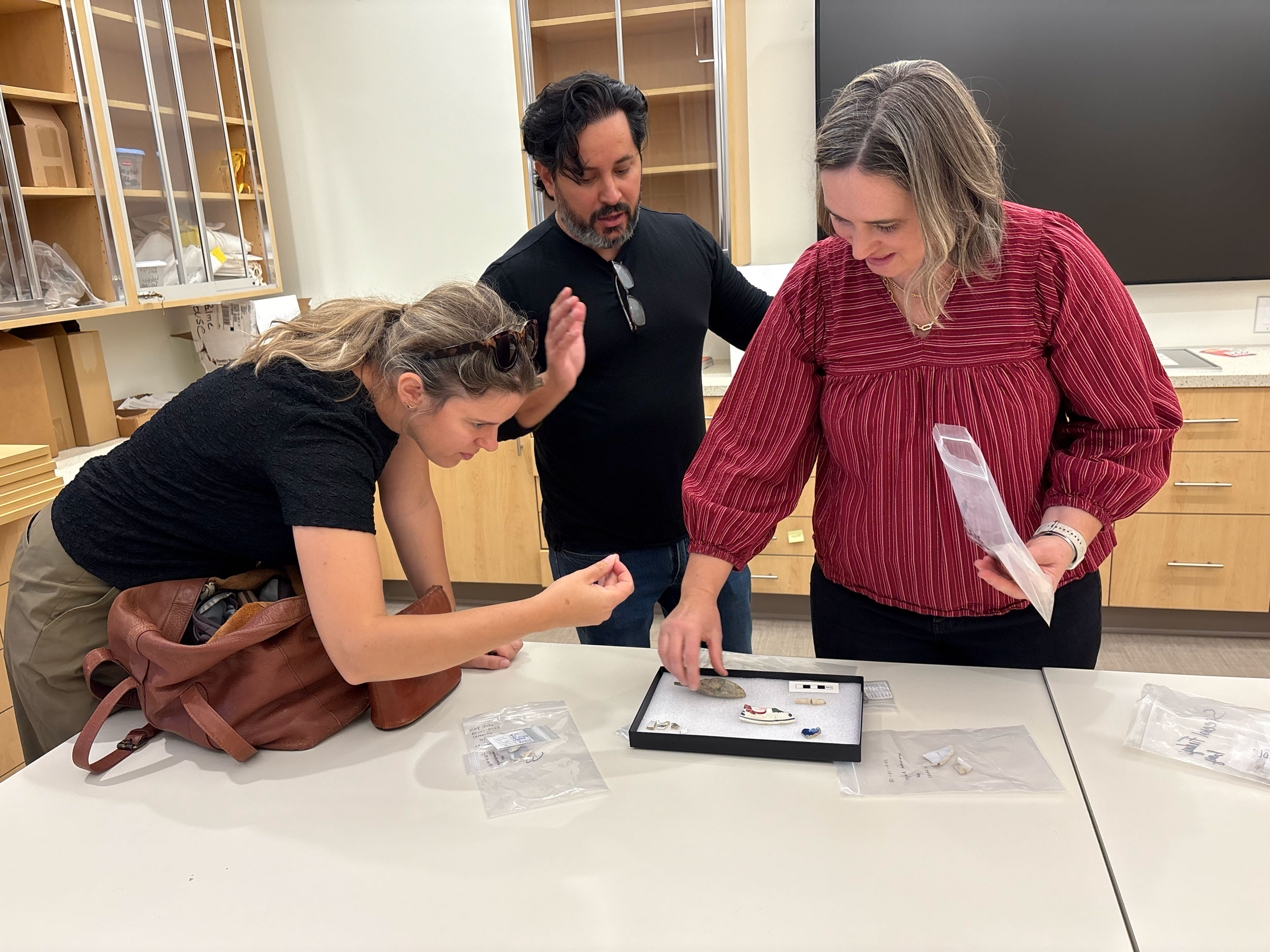

The fragments of the past are carefully bagged and catalogued in a first-floor room in Oden Hall: iron nails, ceramic fragments, broken glass, metal utensils, a human tooth.

Dug up near Middle Path two years ago by a class of students, these items are historical discoveries offering insights into early college life in Gambier and representing valuable, hands-on learning experiences for those interested in archaeology.

“You can read as much as you want, but when you start actually doing it — putting things into practice — it just adds to your learning,” said Elysia Petras, visiting instructor of anthropology.

Petras expects to add even more to the collection of artifacts and experiences this semester now that students in her archaeology methods course have resumed excavations. They’re searching near the Church of the Holy Spirit for more items related to the first buildings on campus, centering on a long gone multipurpose structure believed to have served as a dining hall, chapel and more.

“You really never know what you’re going to find, but we expect to find a lot,” Petras said.

Earlier excavations turned up part of the wood building’s stone foundations; bricks that suggest the presence of a chimney; and hundreds of everyday objects. These included animal bones, personal hygiene items, and pipe stems.

The project originally was conceived by Claire Novotny, associate professor of anthropology, and Tómas Gallareta Cervera, assistant professor of anthropology and Latine Studies. Based on the findings of ground-penetrating radar, they led the first excavations of the site in 2023.

Using picks and shovels, about a dozen students removed the topsoil and then sifted through it with wire screens to search for artifacts. Later, in the classroom, they tried to glean information from the items about the early days of Kenyon, which moved to Gambier in 1828 after being founded by Episcopal Bishop Philander Chase in Worthington, Ohio, four years earlier.

Some of what they found along the edges of the building — which probably stood until the 1850s — surprised them, like all the bones of pigs and cows discovered at the site.

"I thought that maybe they would be hunting more and that we would find a higher concentration of deer bones, but so far we have more examples of domesticated animals,” Novotny said.

Other unexpected clues came in the form of broken ceramics, which students used in class last year as part of Petras’s “Historical Archaeology” course. It turns out — based on the style of the items — that they weren’t produced locally but instead came from the United Kingdom, where Kenyon founder Philander Chase traveled to fundraise for the College.

“A lot of the stuff that they were using was brought from elsewhere. That was the big takeaway,” Novotny said. “They’re on the frontier here, for that time period, but they’re very connected. … There was an effort to not be ‘roughing it’.”

This isn’t to say that life was easy. A human tooth found at the site that was likely extracted because of a large cavity serves as a reminder of the very real medical and health issues that those associated with the College would have faced on the frontier and the limited options they would have had for treatment.

Students have shared their takeaways about local history with members of the local community in various ways. One student, for example, created a coloring book for kids. Area residents also were able to get up close and personal with the excavations this past Saturday as part of Community Archaeology Day.

By being part of the whole process — from discovery to interpretation — students have been able to gain an understanding that goes far beyond what might be possible in the classroom alone, Gallareta Cervera said.

“They get to experience how knowledge is created and see its limitations,” he said. “They learn how you start with an idea, you develop it, you gather the data, you clean it, you curate it, and then you try to come up with conclusions.”

Sophia Procops ’26 couldn’t agree more. The Massachusetts resident was ecstatic to be part of the excavations two years ago and is excited that more students are continuing the work now.

“It was so, so cool,” she said. “I’m a history major, so I kind of was obsessed with the idea that this is local history. You’re looking at it, and you’re like, ‘Oh my God. This is where students used to live.’ … Being able to hold the artifacts and understanding that this was something someone had used, it was very impactful. I am so glad they’re doing it again.”