When most children were obsessed with Pokémon or dinosaurs, Greyson Greischar ’27 says that he was fixated on chemistry.

“My mom has this picture of me holding a chemistry textbook when I was like … 7 or 8 … so it’s been a long process of discovering what chemistry is actually about.”

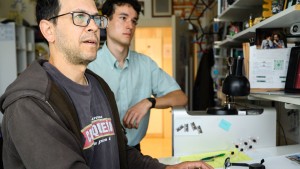

Today, what started as a childhood of wandering wide science museum halls and flipping through old library books has evolved into a much deeper appreciation for what Greischar likes to call the “elegance” of chemistry. He spent recent months pursuing his passion as a Summer Science Scholar in the polymer chemistry lab of Yutan Getzler, professor of chemistry and the Pamela G. Hollie Endowed Chair in Global Challenges.

Polymer chemistry involves the study of large molecules that are composed of repeating subunits known as monomers. Strung together, like beaded necklaces, they form polymers of different shapes — precise and graceful.

Cheap, versatile, and sterile, synthetic polymers surround us in the form of plastics. Problematically, plastic waste is not only incredibly energy inefficient, but results in irreparable habitat damage and causes concern for human health. One culprit is that there are so many different kinds of plastics, making recycling difficult.

But, as Getzler says, “Chemistry has a very, very long tradition of making gold from lead — that is, of taking trash and turning it into treasure.”

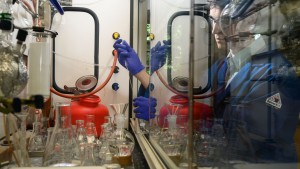

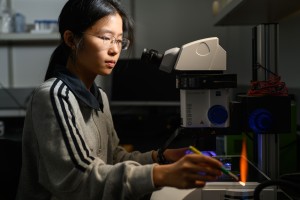

On the third floor of Tomsich Hall, Greischar and his four labmates — wearing matching blue lab coats and accompanied by an upbeat bossa nova playlist — became part of that tradition this summer. There they dedicated themselves to analyzing the problem of plastic recycling through the polymer poly(ε-caprolactone), which can be broken down into its building-block monomer, ε-caprolactone, by a single chemical solution, and then stitched together again into a circular polymer.

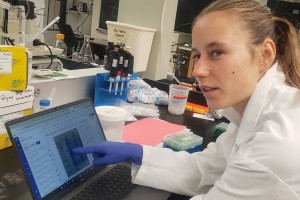

Greischar was working on the first step of this project, what he called the “little monomer factory.” His job was to produce and collect ε-caprolactone derivatives (altered, but related to the original monomer) that were 99.99% pure. The process required a series of thorough steps over several days, resulting in test tubes full of pure monomers.

The work — supported in part by the National Science Foundation and the Dreyfus Foundation — was both collaborative and rigorous, with everything carefully noted in Greischar’s lab notebook. He said he enjoyed the careful attention to detail, even if from time to time the chemicals smelled, as he put it, like “very strong cabbage … rotting cabbage.” It was worth it, as he sharpened his abilities and even got to be inventive with the methodology.

As the summer progressed, Greischar’s love of chemistry grew from an appreciation of its elegance to its practice as a craft, and he was excited to see himself becoming “a more competent scientist.” That is, working with his hands and honing in on a set of skills that will prepare him for his passion of going to graduate school to pursue medicinal chemistry, an interdisciplinary field that combines chemistry and biology to study and develop drugs.

Consequently, Greischar spent the summer collecting the building blocks of polymers as well as those needed for making a scientist. In a way, this was Getzler’s plan all along. “The most important result of my research is not molecules or manuscripts, it is people,” he said. “They’re the valuable thing. They’re the thing that the world needs.”

This article was written by Isabel Braun ’26 as part of the Hoskins Frame Summer Science Writing Scholars program.